Which state of matter is fire?

Keith S. Taber

A trick question?

Education in Chemistry recently posed the question

What state of matter is fire?

This referred to an article in a recent issue of the magazine (May 2022, and also available on line) which proposed the slightly more subtle question 'Is fire a solid, liquid, gas, plasma – or something else entirely?'

This was an interesting and fun article, and I wondered how other readers might have responded.

An invitation

No one had commented on the article on line, so I offered my own comment, reproduced below. Before reading this, I would strongly recommend visiting the web-page and reading the original article – and considering how you would respond. (Indeed, if you wish, you can offer your own response there as a comment on the article.)

A personal response – a trick question?

Ian Farrell (2022) asks: "Is fire a solid, liquid, gas, plasma – or something else entirely?" I suggest this is something of a trick question. It is 'something else', even if not 'something else entirely'.

It is perhaps not 'something else entirely' because fire involves mixtures of substances, and those substances may be describable in terms of the states of matter.

However, it is 'something else', because the classification into different states of matter strictly applies to pure samples of substances. It does not strictly apply to many mixtures: for example, honey, is mostly ('solid') sugar dissolved in ('liquid') water, but is itself neither a solid nor a liquid. Ditto jams, ketchup and so forth. Glass is in practical everyday terms a solid, obviously, but, actually, it flows and very old windows are thicker near their bottom edges. (Because glass does not have a regular molecular level structure, it does not have a definite point at which it freezes/melts.) Many plastics and waxes are not actually single substances (polymers often contain molecules of various chain lengths), so, again, do not have sharp melting points that give a clear solid-liquid boundary.

Fire, however, is not just outside the classification scheme as it involves a mixture (or even because it involves variations in mixture composition and temperature at different points in the flame), but because it is not something material, but a process.

Therefore, asking if fire is a solid, liquid, gas, or plasma could be considered an 'ontological category error' as processes are not the type of entities that the classification can be validly applied to.

You may wish to object that fire is only possible because there is material present. Yes, that is true. But, consider these questions:

- Is photosynthesis a solid, liquid, gas, plasma…?

- Is distillation a solid, liquid, gas, plasma…?

- is the Haber process a solid, liquid, gas, plasma…?

- is chromatography a solid, liquid, gas, plasma…?

- Is fermentation a solid, liquid, gas, plasma… ?

- Is melting a solid, liquid, gas, plasma…?

In each case the question does not make sense, as – although each involves substances, and these may individually, at least at particular points in the process, be classified by state of matter- these are processes and not samples of material.

Farrell hints at this in offering readers the clue "once the fuel or oxygen is exhausted, fire ceases to exist. But that isn't the case for solids, liquids or gases". Indeed, no, because a sample of material is not a process, and a process is not a sample of material.

I am sure I am only making a point that many readers of Education in Chemistry spotted immediately, but, unfortunately, I suspect many lay people (including probably some primary teachers charged with teaching science) would not have spotted this.

Appreciating the key distinction between material (often not able to be simply assigned to a state of matter) and individual substances (where pure samples under particular conditions can be understood in terms of solid / liquid / gas / plasma) is central to chemistry, but even the people who wrote the English National Curriculum for science seem confused on this – it incorrectly describes chocolate, butter and cream as substances.

Sometimes this becomes ridiculous – as when a BBC website to help children learn science asked them to classify a range of objects as solid, liquid or gas. Including a cat! So, Farrell's question may be a trick question, but when some educators would perfectly seriously ask learners the same question about a cat, it is well worth teachers of chemistry pausing to think why the question does not apply to fire.

Relating this to student learning difficulties

That was my response at Education in Chemistry, but I was also aware that it related to a wider issue about the nature of students' alternative conceptions.

Prof. Michelene Chi, a researcher at Arizona State University, has argued that a common factor in a wide range of student alternative conceptions relates to how they intuitively classify phenomena on 'ontological trees'.

"Ontological categories refer to the basic categories of realities or the kinds of existent in the world, such as concrete objects, events, and abstractions."

Chi, 2005, pp.163-164

We can think of all the things in the world as being classifiable on a series of branching trees. This is a very common idea in biology, where humans would appear in the animal kingdom, but more specifically among the Chordates, and more specifically still in the Mammalia class, and even more specifically still as Primates. Of course the animals branch could also be considered part of a living things tree. However, some children may think that animals and humans are inherently different types of living things – that they would be on different branches.

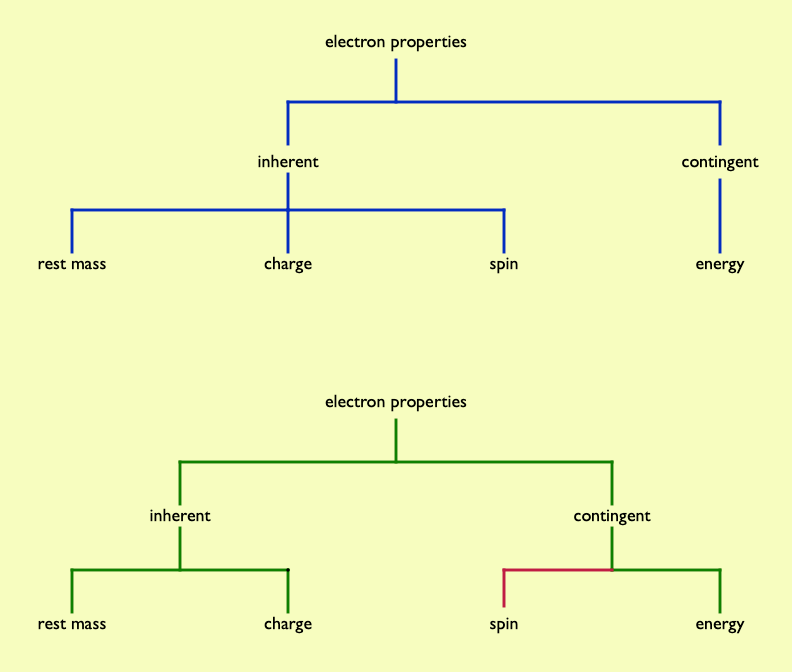

Some student alternative conceptions can certainly be understood in terms of getting typologies wrong. One example is how electron spin is often understood. For familiar objects, spin is a contingent property (the bicycle wheel may, or may not, be spinning – it depends…). Students commonly assume this applies to quanticles such as electrons, whereas electron spin is intrinsic – you cannot stop an electron 'spinning', as you could a cycle wheel, as spin is an inherent property of electrons. Just as you cannot take the charge away from an electron, nor can you remove its spin.

Chi (2009) suggested three overarching (or overbranching?) distinct ontologial trees being entities, processes and mental states. These are fundamentally different types of category. The entities 'tree' encompasses a widely diverse range of things: furniture, cats, cathedrals, grains of salt, Rodin sculptures, iPads, tectonic plates, fossil shark teeth, Blue Peter badges, guitar picks, tooth picks, pick axes, large hadron colliders, galaxies, mitochondria….

Despite this diversity, all these entities are materials things, not be confused with, for example, a belief that burning is the release of phlogiston (a mental state) or the decolonisation of the curriculum (a process).

Chi suggested that often learners look to classify phenomena in science as types of material object, when they are actually processes. So, for example, children may consider heat is a substance that moves about, rather than consider heating as a process which leads to temperature changes. 1 Similarly 'electricity' may be seen as stuff, especailly when the term is undifferentiated by younger learners (being a blanket term relating to any electrical phenomenon). Chemical bonds are often thought of as material links, rather than processes that bind structures together. So, rather than covalent bonding being seen as an interaction between entities, it is seen as an entity (often as a 'shared pair of electrons').

Of course, science teachers (or at least the vast majority) do not make these errors. But any who do think that fire should be classifiable as one of the states of matter are making a similar, if less blatant, error of confusing matter and process. Chi's research suggests this is something we can easily tend to do, so it is not shameful – and Ian Farrell has done a useful service by highlighting this issue, and asking teachers to think about the matter…or rather, not the 'matter', but the process.

Work cited:

- Chi, M. T. H. (2005). Commonsense Conceptions of Emergent Processes: Why Some Misconceptions Are Robust. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(2), 161-199. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1402_1

- Chi, M. T. (2009). Three types of conceptual change: Belief revision, mental model transformation, and categorical shift. In International handbook of research on conceptual change (pp. 89-110). Routledge.

- Farrell, I. (2022). The burning question. Is fire a solid, liquid, gas, plasma – or something elkse entirely? Education in Chemistry, 59(3), 11.

- Taber, K. S. (2008) Of Models, Mermaids and Methods: The Role of Analytical Pluralism in Understanding Student Learning in Science, in Ingrid V. Eriksson (Ed.) Science Education in the 21st Century, pp.69-106. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Note:

1 The idea that heat was a substance, known as caloric, was for a long time a respectable scientific idea.